I could have sworn that I’ve blogged about this before, but apparently I haven’t.

Historical fiction writers are often told to eliminate contraction usage so that the prose sounds “historic.” In truth, contractions— “I’m”, “don’t”, “can’t”, etc.—have been used in spoken English forever. The briefest glance at any Shakespeare play proves that point.

The confusion arises when one looks at novels and other prose from the past. In the opening chapter of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, for example, you will not find a single contraction. Austen uses contractions sparingly in her writing, reserving them mainly for uneducated and/or silly characters. Same with her personal correspondence. She used abbreviations to save space, but few contractions.

This may be an Austen thing, or an English thing, or a “this is a book so I need to write more formally” thing. But prose like Austen’s—and probably Austen’s in particular, given her popularity and the sheer number of contemporary Regency romances out there—is what people expect of Georgian- and Regency-set fiction.

But is formality historical? How did English speakers actually talk in the Georgian and Regency eras? For myself, the question is even more specific: how did Americans talk? The United States’ wealthiest class—merchants, lawyers, plantation owners—were steps removed from England’s aristocratic and gentry classes. We were their country bumpkins.

These questions arose for me while revising In Pieces ahead of acquisition by WhiteFire/Chrism. And I wanted an answer—a good, historically accurate answer!

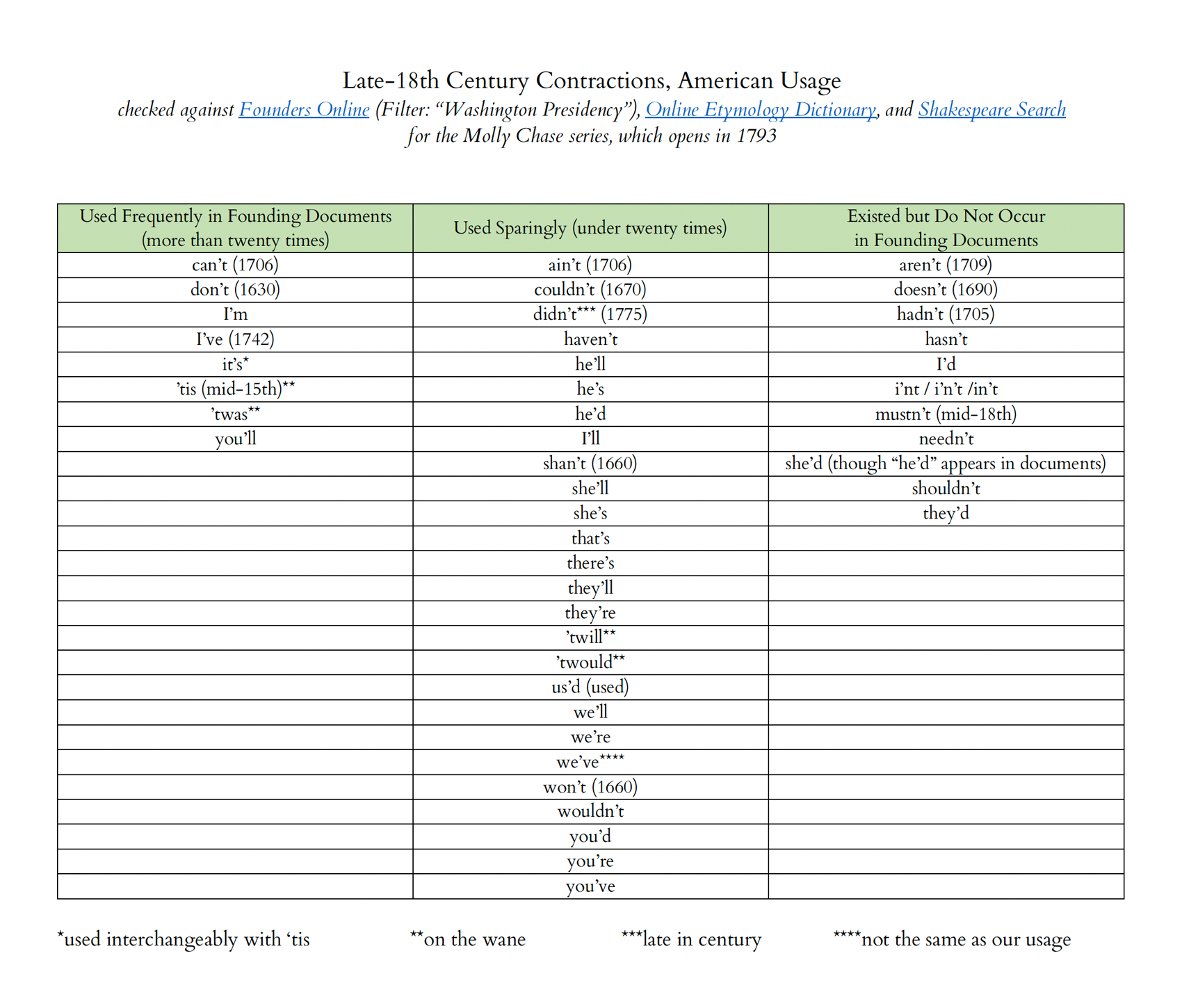

The closest record we have of informal speech is correspondence. My friend and editor Roseanna pointed me to her own research on contractions and American usage. I took her work and went a step further, searching the Founders’ correspondence at the National Archives for not only usage, but frequency of usage.

I also compared and contrasted the Founders’ writing styles. As you can see above, most used contractions consistently. The outliers were Benjamin Franklin, whose letters are practically littered with contractions, and James Madison, who rarely used them, if at all. And if we consider the age, history, and personalities of these two men, we see that this makes sense. Franklin was the son of a candlemaker, he attended school for a few years but never graduated, and he was of an older generation. Madison was younger, he was a Virginian plantation owner, and he was a stick in the mud. Of course his letters were formal to the point of being stilted!

As for American dialects, we don’t have nearly as much evidence. But writing dialect is difficult and fraught with dangers, no matter the time period. So I avoid it.

Armed with this knowledge, I set out not to eradicate contractions, but to employ them for the sake of characterization, as Austen did:

This said, I can’t “write old.” Some authors can write in a historical style and succeed—Eleanor Bourg Nicholson comes to mind. And I wish I could! My writing would be better for it! But my ear isn’t good enough.

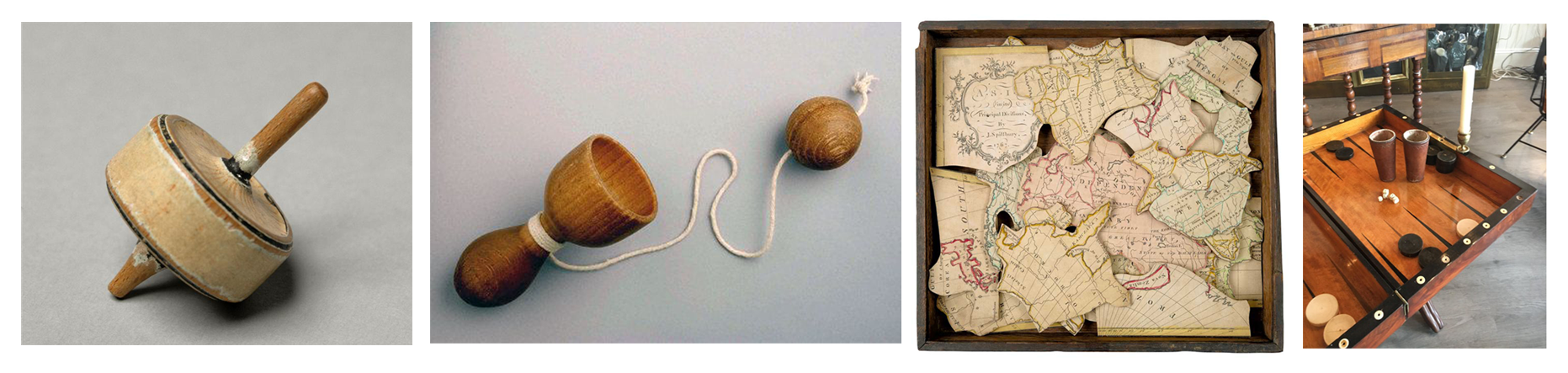

So, like Sigrid Undset, I use contemporary prose to depict a historical setting, leaning on description to depict the period: objects, activities, events, etc. My stylistic goals are modest: write cleanly, avoid anachronisms (with a few exceptions), avoid contemporary sentence cadence as best I can, and sprinkle in Georgian idioms for color. That’s it.

Some think this is a flaw in my writing. They’re not wrong! I love the late Georgian period and “get” it, culturally and otherwise. Yet I have to write around my limitations.

Update 8/15/22:

Another point worth noting, at least with regards the Molly Chase series: Boston is a port town and Josiah Robb is a sailor. As one person in the Patrick O’Brian Appreciation Society pointed out to me, elisions and contractions are natural to nautical speech. Setting and characterization matters!