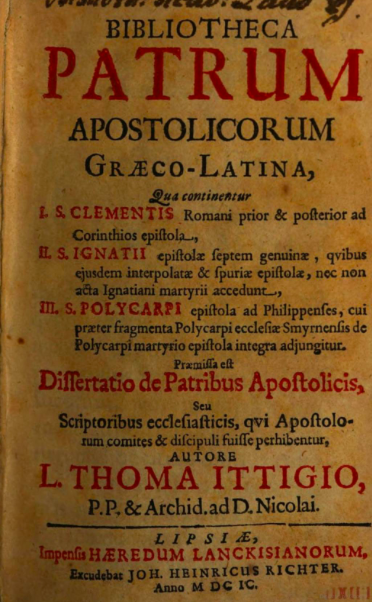

Lin-Manuel Miranda as Alexander Hamilton. (Wikipedia)

My first impressions of Hamilton, now that I—and the rest of America—have finally seen it:

(1) An unavoidable irony: only the well-to-do can afford tickets to see a Broadway show about a penniless immigrant overcoming the odds.

(2) Assigning the role of narrator to Aaron Burr was a stroke of genius. And Leslie Odom Jr. was great in the role.

(3) Miranda did a fantastic job of distilling the complex political crises of the 18th century down to their essentials. As someone writing a story set in the 1790s, I know just how hard this task is. There’s not a single throwaway line in Hamilton.

(4) Every jibe directed toward that hypocrite Thomas Jefferson made me cheer. Or giggle. Or cheer and giggle. My favorite: “He doesn’t have a plan, he just hates mine.” (As my husband says, plan beats no plan, every time.)

My sister recently reminded me that, as an eighth grader, I dared to ask a Monticello tour guide about Sally Hemings. This was before the DNA testing, and I received a not-so-subtle reprimand from the tour guide for being a smart-aleck.

Jefferson. Not a fan.

(5) I had forgotten about Martha Washington naming her feral tomcat after Hamilton. Snort.

(6) My one major critique of Hamilton (and it’s a big one): the story does a poor job of setting up Eliza and Hamilton’s relationship. For me, this undermined both Eliza’s character as well as the story pay-off and Eliza’s finale. If we in the audience don’t know what they had in the beginning, then we don’t experience catharsis as strongly as we ought when their marriage is threatened, nor when they reconcile.

How does the set-up fall short?

The courtship sequence leans wholly on Eliza’s “Helpless.” We don’t see Hamilton falling in love with her, with him as the point-of-view character. The historical Hamilton was smitten with Eliza Schuyler to the point of distraction, as letters written by his fellow officers attest. The musical, however, gives the impression that Hamilton’s affection for Eliza didn’t match hers for him, which just… doesn’t work in a love story. Not having his viewpoint onstage was a huge missed opportunity.

This weakness is compounded by the fact that Miranda pushed aside most of the historical ambiguity regarding Angelica and transformed her into a selfless martyr type, à la Éponine in Les Misérables. Angelica’s powerful story overshadows Eliza’s at Eliza’s expense. Angelica is intelligent and sympathetic; Eliza comes across as an uninteresting nag. (Though, perhaps this is apropos: Angelica overshadowed Eliza in real life, too.) If we keep the Angelica-as-martyr trope, then it’s absolutely essential to build up Eliza’s character and to make Hamilton’s love for Eliza more explicit, right at the beginning.

Did the historical Angelica love her brother-in-law? Yes. Did she suppress her love for her sister’s sake? Yes, as far as we know. Did she and Hamilton flirt? Oh, yeah. Was Angelica his intellectual interlocutor? Yes, though Eliza played her part in helping him in his work, too. But Angelica had been married two years when Hamilton met the Schuyler sisters. Eliza was never a second choice because marrying Angelica was never an option.

Perhaps Miranda doesn’t write a lot of love stories? And therefore didn’t have a handle on love story genre conventions? Someone more familiar with his work might know.

(7) That said, Philip’s death made me tear up. That part worked for me.

(8) The Maria Reynolds affair continues to interest me as a study in human weakness.

(9) I’m curious what people think about Hamilton in light of our current debate on race. Hamilton is triumphalist about both race and America. Does it stand up to critique?

(10) I loved the Broadway references. “I am the very model of a modern major-general…”

(11) My New Yorker husband and I both enjoyed the jabs at New Jersey.

and lastly,

(12) King George III. I laughed so hard. Da-da-da-da-da…!!