Let it be known: I am a lubber. Molly Chase is the story of a girl and her sailor, and not a sea tale. I couldn’t write the latter. But where there are sailors, there are boats, ships, customhouses—and danger.

Great Britain declared war on the French revolutionary government after Louis XVI was executed in 1793. Much of the war was fought on the seas. The impact this had on American commerce cannot be understated. The United States had no navy and only a small standing army, and the War Department had but a handful of employees. Despite President Washington’s declaration of neutrality, American merchant ships were regularly seized by French and British alike, and some 10,000 American merchant sailors were pressed into British naval service between 1793 and the War of 1812.

For the residents of a port town, these dangers were anything but hypothetical.

“Going back out to sea is the last thing I want to do,” Filippo added. “And I do not even have women at home.”

Trade would grind to a halt without able seamen. But what man would want to sail under these conditions? (Adrift, Ch. 55)

The United States Navy was established in 1794, not long after the opening of my story, but an additional four years passed before the original six frigates were completed and commissioned. The job of protecting the ports (and collecting intelligence) fell to the Revenue-Marine and the customhouses. So the 1790s were a particularly vulnerable time for the American merchant service, and we see this playing out in Molly Chase.

Crash Course in Sailing

Twenty-five minutes and you’ll have some vocabulary under your belt. Just don’t go Moana on us and sail beyond the reef—at least not yet!

Crash Course in Full-Rigged Ships

More instructional videos for the dedicated learners among us.

Proof that Sailors are Crazy

Climbing the mainmast = something you won’t be seeing me do.

The Alethea, the fictional merchant vessel on which Josiah Robb serves as first mate, is a brig. Brigs only sometimes carry royals—the smaller set of sails at the very top of a mast, used on larger ships such as the Sørlandet. The Alethea’s masts wouldn’t have been quite this tall.

But tall enough.

*shudder*

Furthermore: Today’s tall ship crews use safety harnesses when climbing aloft. 18th century sailors did not have that luxury.

Nope, nope, nope, nope, nope.

The Penelope

“Twelve-foot clinker-built fishing dory,” Mr. Findley pronounced as Josiah and Mark pulled back the coarse canvas tarpaulin covering Grandfather Robb’s boat, sending years of dust into the pungent stable air. Mark had mentioned the boat to his father as soon as they arrived home, and Mr. Findley had insisted on showing her to them immediately, despite the late hour. “But not the typical dory. She’s double-ended with a shallow keel, and she’s built with some heft to her, as you see.”

Josiah looked her over. “She’s well-proportioned.”

“Then she’s perfect for you,” Mark deadpanned.

“’Tis your grandfather’s design,” Mr. Findley said before Josiah could pummel his son… (Adrift, Ch. 14)

With In Pieces, I wrote around any actual sailing, focusing instead on activities I felt adequate to describe: ship repairs, ship chores, lading and unlading, and discreet movements such as climbing down from the maintop. (Windward shrouds, check.)

But the plot of Adrift demanded that Josiah spend time on the water.

Sailing.

In a boat.

In an eighteenth century boat.

Grandfather Robb’s Penelope almost did me in. All I knew was that Josiah needed something more than a fishing boat. But 1793 Boston was not a time and place for pleasure craft, and besides, who am I to figure this out? Lubber! I have it here, embroidered on the front of my hat! L-U-B-B-E-R.

Gunter rigged Lobster 12.5, which, if it isn’t a peapod, resembles one. And I really can’t believe I found a near-perfect example on Wikipedia, of all places.

Thank the Almighty I am fond of self-deprecating humor, because had I not shared about my boat research woes on Facebook, I would never have been introduced to the Patrick O’Brian Appreciation Society, without which this book may never have been written. Need an eighteenth century boat? Ask avid readers of Patrick O’Brian. You will get a boat.

As described, the Penelope is a Maine peapod, a traditional New England fishing boat. The name peapod didn’t come into use until the late 19th century, so I call her a dory, as dory was an eighteenth century American catch-all term for any small craft. The Penelope was designed for rowing first, with sailing as an afterthought. After the day’s fishing was done, Grandfather Robb might have set a spritsail (a simple sail) with the hope of catching a little wind as he headed home.

Josiah, however, was initially told to buy a boat for the sake of his sanity. He’s not interested in fishing. He needs his time on the water, and he wants to go fast. Because he’s Josiah Robb. So, as part of the Penelope’s restoration, Josiah adds a gunter rig, as seen here, where the sail is attached to a vertical yard which is then raised above the mast. (He also adds a daggerboard.) That I have him choosing a gunter rig is a slight anachronism, as the earliest known usage was the 1830s. But today’s peapods are sometimes gunter rigged, and a gunter rig makes for more sail and also allows for a headsail, and more sail = more fun. Or so it seemed to me.

Custom House

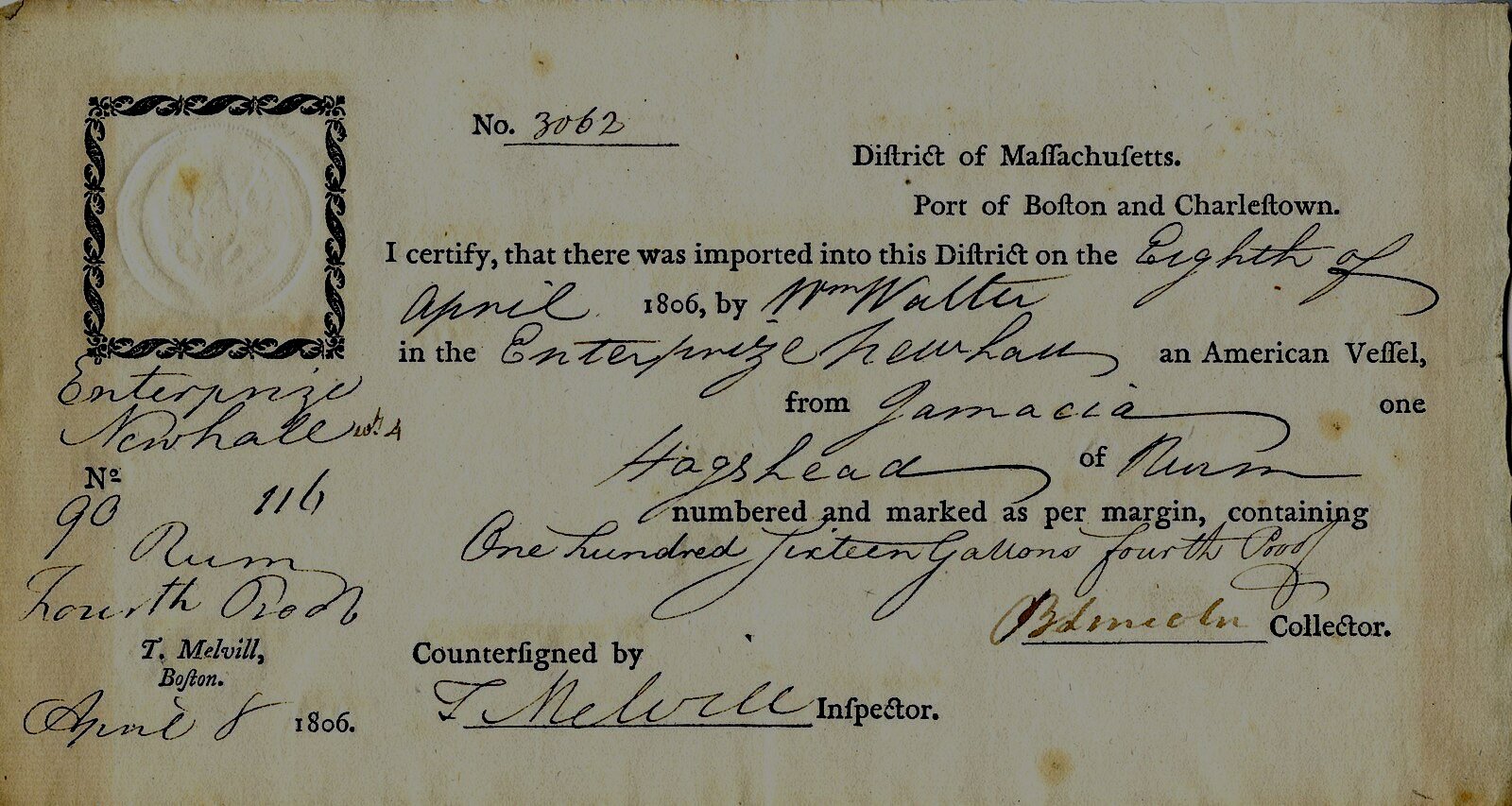

Customhouse paperwork signed by Benjamin Lincoln and Thomas Melvill.

As I mention above, not only did the United States customhouses levy taxes (the only source of income for the federal government, incidentally), but they played an important role in national security. The officers and inspection crew, along with the Revenue-Marine, kept track of every ship, every person, and all goods that came in and out of the country.

Immediately after Washington declared his Proclamation of Neutrality, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton wrote to the Collectors of Customs, asking them to report all suspicious activity, especially the armament of vessels. In Boston, this task would likely have fallen to Major Thomas Melvill, Custom House surveyor and third officer in charge, and the tidewaiters (cargo inspectors) under his supervision. The collection of intelligence would be a natural extension of their duties.

The Ship Mount Vernon: Records of a Salem Vessel in 1803

Online exhibit at the National Archives at Boston

Tax Collectors There Must Be: Inside Boston Custom House

Taxes: America's favorite controversial topic. This is no less true today than in 1789, when the First United States Congress was faced with the task of figuring out how to raise revenue without ticking everyone off.

On Young Sailors Becoming Self-Made Men

Above him, the ship’s cargo boom swung a barrel of Madeira wine toward the dock. His shipmates handled the boom’s runners from the deck, fighting to keep the barrel steady against the bracing harbor wind. Their bosun, Isaac Lewis, directed the barrel’s unlading from his perch on the maintop. Another mate, Josiah’s best friend Filippo Lazzari, waited for it on the dock, as did old Charles Putnam from Custom House. The wine was Josiah’s—he bought five pipes of it while overseas. Captain Harderwick never minded lending cargo space, so long as he got his cut of the profits. (In Pieces, Ch. 4)

At the opening of In Pieces, Josiah Robb is not only first mate of the Alethea, but a small-time merchant himself. When I first wrote this scenario, I merely assumed it was possible. Why wouldn’t a merchant-captain let his young officer try his hand at turning a profit? How would anyone move up in the world, unless more established businessmen helped him out?

As I continued my research, I discovered this scenario was not only probable, but common. Shipowners sometimes gave their seamen a small amount of capital for their own ventures. Some of these sailors made enough to become shipowners themselves.

From Nothing to Something: Nathaniel Silsbee

A historical precedent for Josiah.

When Lubbers and Sailors Meet

Josiah unshipped his oars. “Time to make sail. You stay seated and watch.”

“Teach me, O Wise One.” Mark saluted, his other hand holding his oars, blades flat on the water.

“First things first.” Josiah slid his oars onto the hull, then looked over the stern to make sure the rudder’s pintles hadn’t pulled free of their gudgeons. The metalwork was new, and though he was no Isaac Lewis, he thought himself a decent carpenter. But the old girl was several decades old, and he was of a mind to check everything twice over before getting underway. Thus far, the Penelope was holding together. “Good.” He pivoted halfway and gestured. “This is a tiller. It turns the rudder.”

Mark glared. “I’m a lubber, not an imbecile.”

“One never can tell. Best to name everything.”

“Son of a mongrel.”

“My grandsire’s ark is what’s keeping you afloat. You can pull in your oars now. We’ll switch places.” (Adrift, Ch. 32)

The following blog post comes with a disclaimer: Any cheekiness is of the college rivals variety, and not directed at the military itself. I do value our servicemen.

No, truly! I do!

A True Story, with Creative Embellishments, Inspired By My First Reading of Patrick O’Brian’s Master and Commander

I know Jack and Stephen.